Last Updated on December 30, 2025

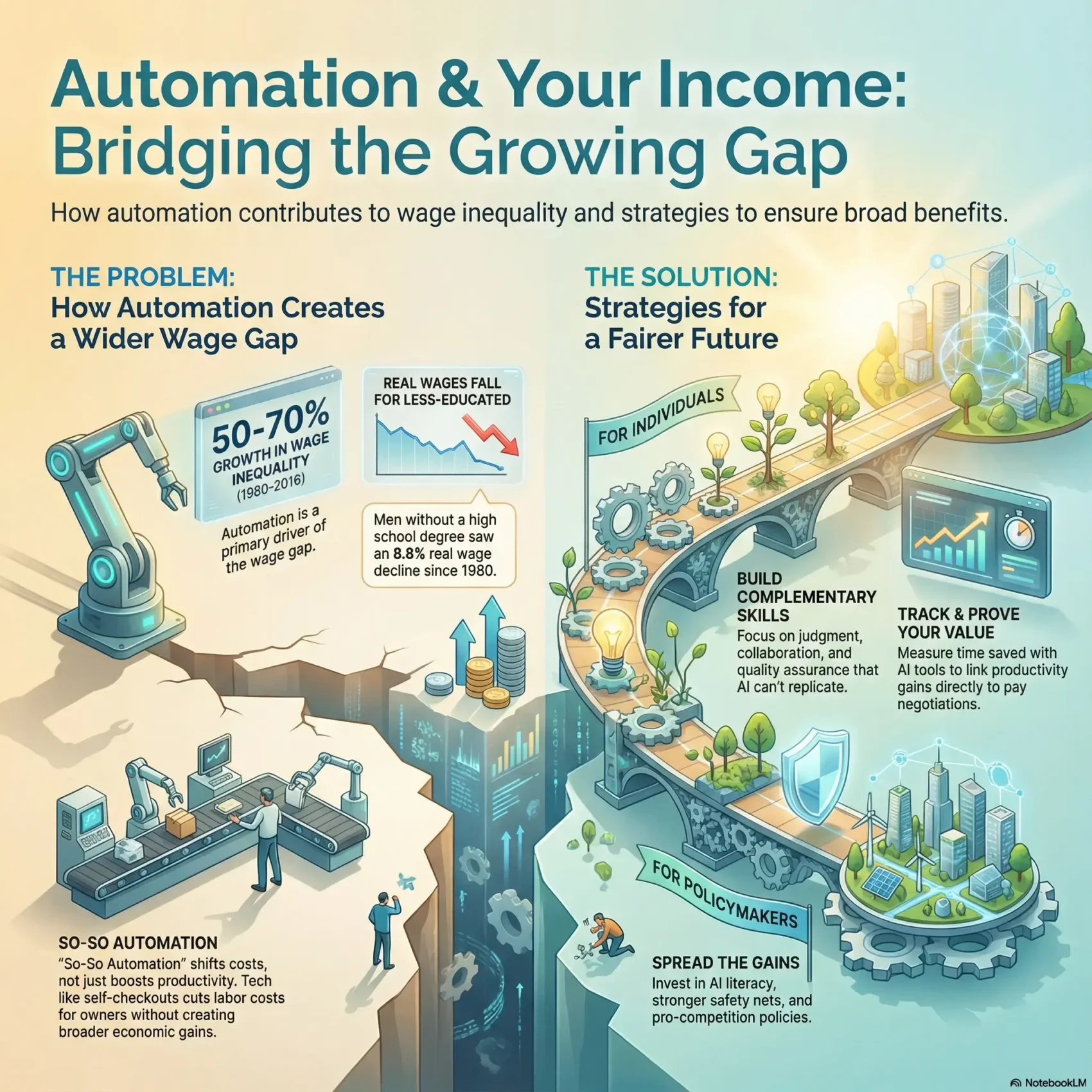

This brief guides you through how automation shapes income and the risks it poses for workers in the U.S. You’ll see clear evidence from researchers Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo that links past decades of change to today’s wage shifts.

Technology has driven massive growth in GDP per person for centuries, from steam power to electricity. Yet recent studies show gains often land with higher-paid, computer-based roles, while less-educated workers faced real wage declines since 1980.

You will get a compact roadmap: what the data says about impact on wages, why market structure matters, and practical steps you can use to protect your income. The goal here is not fear; it is to help you position your skills so productivity benefits reach more people and places.

Key Takeaways

- You’ll learn why research ties much of the rise in wage gaps to automation.

- Evidence shows men and women without a high school degree saw real wage falls since 1980.

- Productivity gains may first favor computer-based, higher-income roles.

- Market concentration and production choices shape who benefits from growth.

- You’ll get practical signals and skill priorities to protect your income.

Why automation and inequality matter for your financial future

The ways firms adopt new tools can change your work, wages, and long-term income. Recent studies link tech adoption to more than half of the rise in wage gaps since 1980. That effect hit less-educated workers hardest.

What this means for you: if productivity gains go mostly to capital or high-paid roles, your pay may lag even as output grows. Unequal access to AI tools and training widens the gap in bargaining power and employment stability.

Short-term risks include jobs that get enhanced for higher-income, computer-based roles while in-person or manual tasks face slower gains or displacement.

- Track how your industry adopts new tools and where productivity lifts land.

- Invest in skills that complement AI-like systems to raise your income prospects.

- Watch wage trends versus productivity so you can negotiate or pivot early.

For a deeper look at how tech reshapes jobs and policy choices, see this report on automation and jobs.

Defining the terms: automation, productivity, wages, and inequality

Clear definitions let you know what to watch for at work. Start by separating tools that replace narrow tasks from those that lift total output. That split shapes who wins from new tech.

Task automation versus productivity-enhancing technology

Task-focused systems substitute specific duties and often lower payroll without much gain in overall productivity. Acemoglu calls many recent deployments “so-so automation” because they shift work rather than expand what the economy can produce.

Labor share, capital share, and how income is divided

Labor share measures how much of total output goes to workers; capital share goes to owners. When capital captures more, your wages can lag even if productivity rises.

- Tasks within jobs differ in exposure; that mix sets your risk.

- Watch research on who captures gains to judge likely impacts on your income.

- Knowing these terms helps you plan which skills to strengthen.

From looms to LLMs: a brief history of tech, jobs, and the economy

From water frames to large language models, tech has repeatedly reordered jobs and pay. These shifts raise growth but also reshuffle who benefits.

The Industrial Revolution, Luddites, and sector shifts

The first machines in British textiles sparked the Luddite protests when workers feared displacement. The uprisings were suppressed by 1816, yet they highlight an early clash between labor and new tools.

Transitions: agriculture to manufacturing to services

Over decades, workers moved from agriculture into factories, then into services. Each transition changed which skills mattered and which jobs rose or fell.

Rising GDP per capita and living standards over time

GDP per person climbed dramatically after the steam engine and electricity. That long-run rise lifted living standards across the economy.

When productivity outpaces pay: the post-1980 divergence

Since the 1980s, productivity has outpaced wages. Firms like Foxconn replacing many workers with robots show how fast substitution can occur.

“Technology drives growth, but policy chooses who shares the gains.”

- Growth often raises output faster than pay.

- Sector shifts reshape labor demand and skills.

- Historical patterns help you prepare for today’s transitions.

Evidence check: what research says about wage gaps since 1980

Data-driven work measures how task change reshaped pay across groups since 1980. You get clear evidence from a major study that links firm-level task shifts to rising gaps in income.

Key findings: the paper estimates that task substitution explains roughly 50–70% of the growth in between-group wage inequality from 1980–2016. The authors use BEA industry figures, robot adoption measures, and Census/ACS data covering about 500 demographic subgroups.

- The study finds large measured effects for less-educated workers: roughly −8.8% for men and −2.3% for women without a high school degree (real terms).

- Combining industry-level data with adoption measures helps isolate causal links between firm choices and worker outcomes.

- These results show how changes in tasks drove much of the observed rise in wage gaps, while other forces like declining unions or concentration also played roles but do not fully explain the pattern.

Use this research as a practical signal. Compare the study’s industry mix to your local labor market to judge exposure. Then focus training on roles that raise your resilience to task shifts.

“So-so automation” versus genuinely productivity-boosting technologies

Not all tech lifts what the economy produces; some simply moves work around. That split shapes who gains from new machines and who loses hours or pay.

Self-checkout kiosks as a labor-shifting device

Self-checkout offers a clear case. Stores cut labor costs by asking customers to scan items, but overall productivity often stays flat.

That matters: lower payroll shows up as corporate savings, not higher wages or better service for most workers.

Who benefits when productivity barely moves?

When output does not rise, owners and investors tend to capture the gains. Low-skill service workers face the largest losses.

“Self-checkout does not significantly increase productivity but does reduce labor costs and has fairly large distributional effects.”

- Check if tech in your job cuts costs or raises output.

- Reframe tasks toward value that machines or customers cannot easily perform.

- Watch how firm incentives in your industry favor cost-cutting over broad productivity gains.

Polarization of work: where middle-wage jobs went

Job growth has shifted toward high- and low-pay roles, leaving the once-robust middle thinner than before.

Research by David Autor shows a clear rise in top-tier professional roles and in low-wage service work from 1989 to 2007. Middle-wage clerical and production positions declined as routine tasks changed.

This matters for you: if your current job relies on routine tasks, it faces higher risk of replacement.

Growth at the top and bottom, hollowing out the middle

Routine task substitution hit clerical staff and many factory workers hardest. At the same time, demand grew for analytic occupations and for retail, food service, health aides.

- Local sectors shape exposure; some regions saw severe employment losses.

- Polarization reduced bargaining power for many workers, pressuring wage growth.

- Practical pivot: focus on tasks that complement tools or require human judgment.

Industries and tasks most exposed to machines and algorithms

Look at which industries pick machines first — it tells you where jobs will shrink or shift.

Robots in manufacturing and electronics

Manufacturing and electronics lead in robot use. U.S. robot adoption from 1993–2014 replaced many roles on assembly lines.

Large firms like Foxconn show the pace: robot fleets can cut headcount quickly. That change reshapes routine shop-floor duties into monitoring, repair, and quality checks.

Services under pressure: retail, call centers, and customer support

Services are under rising pressure too. Self-checkout and AI systems reduce staffing needs in retail and call centers.

Klarna’s reported shift — software taking on the work of 700 agents after layoffs — shows how fast employment can change when costs and reliability favor machines over people.

- Which sectors deploy robots most: manufacturing, electronics, then select logistics firms.

- Common exposed tasks: rules-based, repetitive, and data-heavy work.

- Remaining roles often become exception handling, oversight, or customer relations.

Practical check: list your daily duties. If they are repeatable or scripted, your exposure is higher. If they require judgment or relationship skills, you stay more valuable.

Automation and inequality

Who does which task matters for how income flows. When firms shift duties from people to machines, pay can move toward owners or high-paid roles instead of workers. That dynamic drives much of the rise in inequality since 1980.

Research shows effects concentrate by education: lower-skilled workers faced larger real wage drops while capital owners captured bigger shares of gains.

Market forces like concentration and weak bargaining raise the odds that productivity lifts stay in margins. In tight markets, dominant firms scale returns and widen gaps faster than in competitive ones.

- Check whether gains in your sector raise your wages or sit as profits.

- Focus upskilling where task exposure is high for lower-paid roles.

- Watch local labor institutions; stronger bargaining often means a fairer share of income.

“It’s not only net jobs that matter but who benefits when tasks move.”

Use this view to plan career moves and to weigh policies that could spread gains more broadly across workers and communities.

How AI changes the near-term: productivity boosts and who captures them

When AI plugs directly into digital workflows, higher-paid knowledge roles tend to benefit first. That pattern comes from where exposure is highest: many GPT-like systems are easiest to embed into computer-based jobs. Firms with digital toolchains see faster task gains in those roles.

Why higher-income, computer-based roles gain first

Research finds exposure to GPT-4-style systems peaks near occupations that pay about $90,000 and stays high into six figures. These jobs already run on code, cloud services, and text tools, so integration is faster.

Result: firms capture immediate productivity gains where tooling fits smoothly, often increasing output before wages move.

Task-level gains for novices in white-collar jobs

Trials in coding, writing, and customer support show novices get bigger task boosts than experts. In one Fortune 500 support center, GPT-enhanced software raised productivity by 14% on average, with larger improvements for less-experienced agents.

What you can do: test prompts that speed routine work, build simple quality checks, and track time saved so your team can link gains to pay or promotions.

- Assess which tasks in your job match AI strengths: repeatable, digital, text-heavy work.

- Push for incentives that share productivity gains—bonuses, raises, or career steps tied to output.

- Use small QA routines to ensure higher output also means higher quality, not just higher expectations.

“Within-occupation boosts matter, but they do not automatically change who wins across the market.”

When automation shifts returns from labor to capital

As machines take on end-to-end production steps, revenues can drift toward owners rather than paychecks. This change matters because it can reshape who benefits when firms cut costs or scale output.

From helping hands to full task takeovers

Shift in scope: early tools often assisted human work. Newer systems can finish whole tasks without steady human input.

Result: a larger share of value moves to capital owners if total production does not grow enough to hire more people.

Falling demand for human labor and wage pressure

When firms need fewer staff, labor demand falls and wage growth weakens. Wage premiums for skills that a machine can match tend to drop.

Roles often change toward oversight, exception handling, or quality checks. Those positions do not absorb all displaced workers.

- You should watch pilots that move to full deployment as early signals of impacts.

- Assess whether your firm raises productivity or simply reduces payroll before it scales hiring.

- Plan to build judgment, complex coordination, and domain expertise to stay resilient.

“When end-to-end systems replace core tasks, who owns the gains matters more than how fast the tech works.”

Market concentration and winner-take-most dynamics

Dominant firms can turn small technology advantages into long-lasting market power that reshapes places and pay. When scale and network effects kick in, one firm’s edge grows faster than rivals can match. That concentrates the market and redirects where growth lands.

Increasing returns, scale effects, and dominant players

In tech, increasing returns mean bigger firms get cheaper at serving more customers. Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft show how platforms and data moats lock in advantages.

This matters for you: concentrated markets can weaken your bargaining power. If a few firms set prices and hiring norms, wage growth can lag even as productivity rises.

- How value shifts: scale lets owners and top roles capture more income while average pay stalls.

- Local effects: in places with a dominant employer, career mobility and wages can drop.

- Policy levers: competition enforcement and labor standards can rebalance outcomes without halting growth.

“Winner-take-most dynamics channel profits to capital owners and top talent, changing who benefits from new technologies.”

Check your local market and industry mix to judge exposure. That helps you plan which skills to build and where to seek better opportunities in the economy.

Geography and demographics: who’s most at risk in the U.S.

Place matters: where you live and your background affect how new tools hit your job prospects. Use simple local signals to judge exposure and to plan moves that protect your income.

Education levels, age cohorts, and immigration status

The Acemoglu‑Restrepo study links exposure across 49 industries to outcomes for roughly 500 demographic groups. This data shows lower education groups faced larger wage and employment drops from 1980–2016.

Young and older cohorts often fare differently. Less-educated younger workers may face weak wage growth while older workers have fewer chances to retrain. Immigrant workers’ outcomes vary with industry mix and job access.

Regional labor markets and sectoral makeups

Regional labor market structure shapes risk. Counties heavy in manufacturing saw sharper job losses; places dominated by services saw different pressures.

- Check your local industries: a manufacturing hub has different exposure than a service center.

- Spot leading indicators: firm-level adoption, vacancy trends, and wage growth.

- Local action: employer partnerships, training programs, and mobility options help workers adapt.

“Targeted, place-based strategies help cushion shocks and expand opportunities for exposed workers.”

Data snapshots you should know

Quick, clear metrics help you spot which groups lost ground and which roles gained from recent shifts in tools and tasks. Use these snapshots to judge your own exposure and to guide practical next steps.

Wage effects on workers without a high school degree

Headline: since 1980 men without a high school degree saw about an 8.8% real decline in pay; women in the same group fell roughly 2.3%. These are real wage changes, not nominal figures.

This research and the underlying study combine industry data with demographic samples to show how lower-education groups lost income relative to others. Use the numbers as a quick risk gauge for local labor markets.

Exposure to GPT-like systems across occupations

Exposure to GPT-4-style productivity gains clusters in higher-paid roles. Measured impact peaks near occupations that pay about $90,000 and stays high above six figures.

A Fortune 500 support center trial showed a 14% productivity rise on average, with larger boosts for less-experienced workers within the same job. That means within-role gains can favor novices more than veterans.

- You’ll get headline metrics on how less-educated workers’ wages shifted since 1980.

- See where AI exposure clusters across the income distribution for jobs and employment types.

- Review task-level evidence from enterprise settings to spot which workers gain most.

- Connect these points to your job to estimate potential exposure and wage implications.

“Interpret the numbers with nuance: short-term productivity lifts may not translate to long-term income gains for everyone.”

Practical tip: track local vacancy trends plus firm-level pilots. Those signals change fast; newer data will help you prioritize skills that align with favorable productivity–wage dynamics in your region.

Scenarios for the next decade: steady assist, rapid automation, or something different

Over the next decade, plausible paths split between steady worker assist, sudden task replacement, or a mix we have not yet seen. Each path has clear implications for your career, savings, and mobility.

Assistive AI that augments workers

Steady assist boosts productivity by helping you do tasks faster while demand keeps pace. If firms share gains, your pay and job quality can rise with growth.

Automation tipping points in services

Some services—customer support, scheduling, routine processing—may hit reliability thresholds. When that happens, firms may cut headcount quickly if demand does not increase to absorb new output.

Implications if general-purpose AI scales further

If general systems widen scope across many tasks, the economy’s task mix could shift sharply. Labor demand may fall in some roles while higher-end work grows.

- Watch signals: cost curves, adoption rates, and performance benchmarks.

- Prepare moves: cross-skill, role redesign, or shift to adjacent sectors.

- Align finances: increase savings, reassess risk tolerance, and plan retraining time.

“Transition speed matters: fast shifts can outpace retraining and safety nets.”

Policy playbook: spreading gains and cushioning shocks

Policy determines if productivity lifts flow into paychecks, public goods, or corporate margins.

Good public choices make the difference when new tools reshape the labor market. You need clear steps that widen access to benefits while cushioning those hit by change.

AI literacy, education, and training for new tasks

Invest in short courses, on-the-job mentoring, and sectoral partnerships so more workers can use new systems at work.

Targeted education increases placement rates in higher-pay roles within services and manufacturing hubs.

Strengthening safety nets and transition support

Improve unemployment insurance, wage insurance, and relocation aid to bridge job losses to reemployment.

Support must match real adoption timelines so displaced people can retrain without income collapse.

Competition policy and worker bargaining power

Enforce rules that limit dominant firms and boost collective bargaining. Stronger market checks help ensure productivity raises reach paychecks.

Tax policy to fund mobility and public goods

Adjust revenue tools to fund training, mobility grants, and local public goods that increase opportunity across places.

“Smart policy complements innovation, aligning incentives so growth reduces inequality rather than deepening it.”

- Fund AI literacy programs with targeted tax revenues.

- Link support to measurable reemployment outcomes.

- Use competition tools to protect regional labor markets.

What you can do now: skills, tools, and career positioning

Little skill bets and routine tracking make it easier to capture productivity gains at work. Start with small, measurable moves that prove value to your team. These steps help you stay relevant in a shifting market and protect your employment prospects.

Build complementary skills and use AI at work

Focus on practical skills: prompting, quality assurance, domain judgment, and collaboration. These add immediate value and pair well with new technology.

Evidence: task-level studies show novices in writing, coding, and customer support see large gains when they use tools well. Follow that model: practice on a few tasks, measure time saved, and record outcomes.

Track industry signals and firm-level adoption

- Monitor pilot programs, vendor deals, and hiring changes in your sector of services and manufacturing.

- Map daily tasks into automatable versus uniquely human categories and shift focus toward higher-value activities.

- Use certifications, a portfolio, and measured outcomes to turn improved productivity into better job and pay talks.

- Build optionality by exploring adjacent roles where your skills transfer if your niche changes.

Network with peers at firms that adopt tools responsibly. Set a steady learning cadence so you keep pace with model updates and changing labor needs. These simple moves raise your odds of staying a valued worker.

Conclusion

This conclusion pulls the main lessons together so you can act with clear steps and calm urgency.

Over two centuries, technology helped lift living standards, yet since the 1980s a steady rise in productivity has not always matched pay. Recent research links much of the recent increase in wage dispersion to automation, which can shape who captures gains.

What to do: build transferable skills, monitor firm pilots, and press for policies that share growth fairly. Watch whether gains boost your income or flow to owners; that shift changes labor’s share and the broader economy.

Take these steps early. With smart choices, you can capture growth while limiting worse inequality impacts.