Last Updated on December 16, 2025

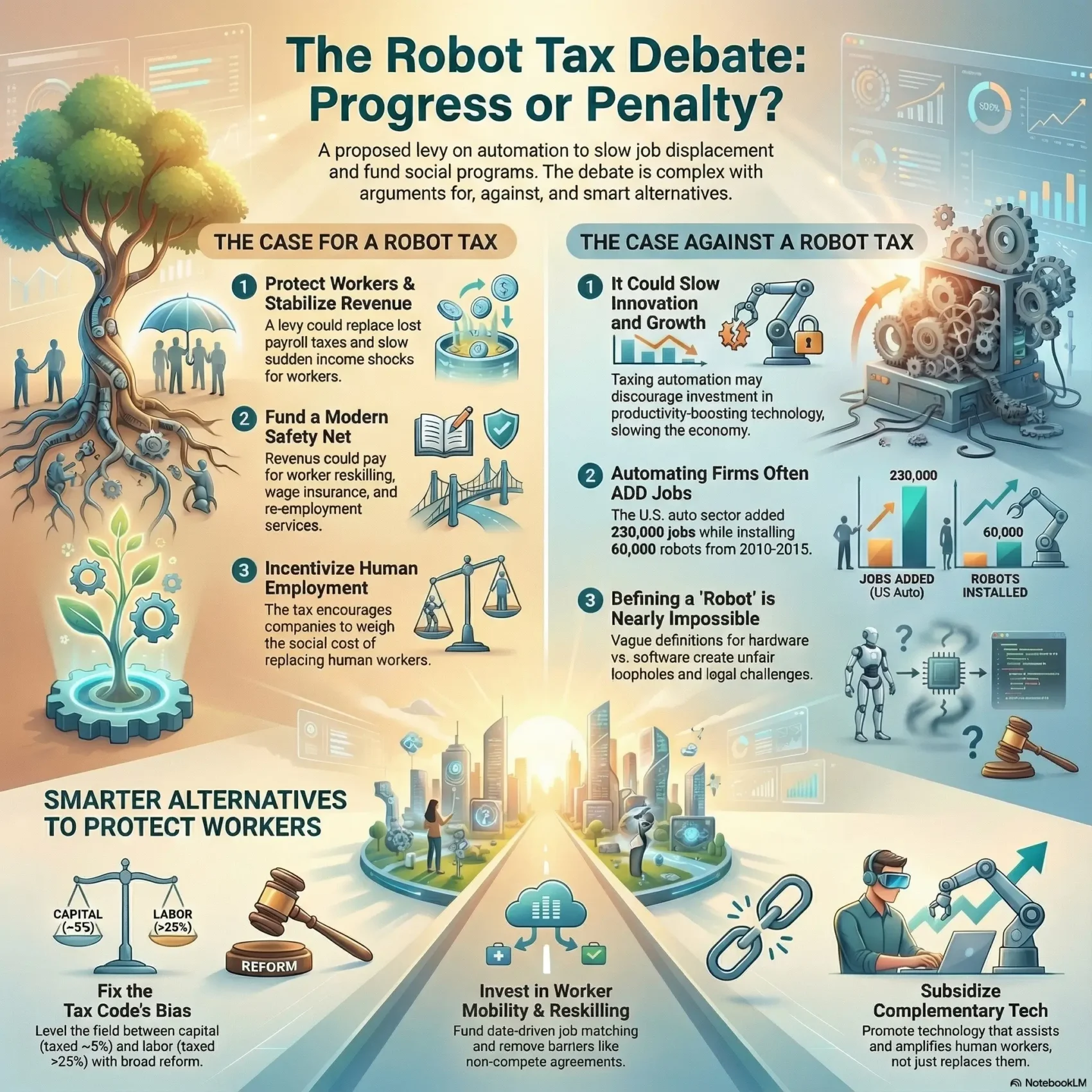

You’re stepping into a timely conversation about whether charging firms when they replace a worker with a machine could shield jobs and fund social programs. Prominent voices like Bill Gates and former New York Mayor Bill de Blasio helped push this idea into the public eye.

The proposal aims to slow displacement and restore payroll revenue, but evidence is mixed. Research to August 25, 2021 shows firms that adopt machines in places like Canada, France, and Spain often add jobs and raise productivity, even as lagging firms lose ground.

The core choice is simple: do you tax profits or the tools that make them? The U.S. code currently favors capital—about five percent effective rates for equipment and software versus much higher rates on labor—so many argue broader reform could work better than a blunt robot tax.

Key Takeaways

- The idea gained traction from public figures and aims to protect workers and income.

- Evidence shows adopters of automation often grow jobs and productivity.

- Taxing tools versus profits raises questions about competitiveness and growth.

- U.S. tax rules favor capital, prompting calls for wider reform instead of a narrow levy.

- You’ll weigh politics, firm incentives, and practical fixes like reskilling.

Why you keep hearing about a robot tax right now

You’re hearing renewed calls for a levy on automation because advanced systems moved from lab demos to shop floors and service lines.

High‑profile names such as Bill Gates and Mayor Bill de Blasio pushed the idea into headlines. That attention makes the proposal feel like a natural policy response to protect workers and preserve jobs.

At the same time, industry groups push back. The IFR and research from McKinsey stress that more than 90 percent of roles aren’t fully automatable. They point to the U.S. auto sector adding about 230,000 employees while installing 60,000 robots during 2010–2015.

“Taxing profits, not the machines, better preserves competitiveness,” says one industry view.

You’re seeing policymakers weigh trade‑offs: will a levy slow investment and innovation or shore up payroll revenue as employment patterns shift? International mobility of capital means countries must factor coordination into any design.

- Short run: headlines and politics amplify the idea.

- Evidence: adopters often grow; non‑adopters shrink.

- Policy trade‑off: revenue versus growth and competitiveness.

Your search intent: what you want to know about the robot tax debate

You want a clear sense of what a levy on automation would do to workers and firms. In plain English, a robot tax would charge companies that replace people with machines. The goal is to slow displacement and recapture payroll revenue to fund retraining and support.

Quick takeaway: what a robot levy is supposed to do

Short version: it promises funds for reskilling, a safety net for displaced workers, and an incentive for companies to keep people in the loop.

- Definition: a fee when firms swap a job for automation.

- Likely impact: evidence shows adopters often expand employment, so a blanket levy could backfire if poorly targeted.

- Policy clarity: what counts as a machine, who pays, and when the levy applies are the real choices.

- Example: industrial arms versus office software bots — treating both the same raises fairness questions.

- Future need: you must weigh whether this is a temporary bridge or a long‑term policy, and how capital is treated versus labor.

“Design matters: targeted support beats blunt levies.”

Defining “robot” in policy terms before you tax it

Defining what exactly counts as an automated system is the first policy battle you’ll face. If the rule is vague, it creates winners and losers across sectors.

ISO 8373 gives a clean start: an industrial robot is an “automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose manipulator with three or more axes.” That covers welding arms and many factory manipulators.

Industrial robots vs. software bots: ISO 8373 and RPA aren’t the same

Software bots like RPA mimic tasks without physical axes. Including them would sweep in accounting and bill‑pay programs.

Edge cases: driverless forklifts, CNC, and warehouse systems

The U.S. Census survey excluded AGVs, driverless forklifts, AS/RS, and CNC gear from some counts. That shows how edge cases can slip through or get swept in.

Why fuzzy definitions skew which industries and jobs pay

If you exclude driverless forklifts, warehouses might avoid a levy while factories with welding arms pay. That could shift investment and capital decisions and reshape where companies locate.

“Precise terms reduce loopholes and litigation risk.”

- Example: states with as much as 15 percent manufacturing employment could litigate definitions.

- Result: unclear lines invite re‑labeling and inefficiency.

- Policy note: many experts prefer broader capital taxation to a brittle robot label.

What the evidence says about robots, jobs, and productivity

Empirical studies now give you clearer signals about how automation affects employment, firm performance, and consumer welfare. Firm-level work across countries shows adopters often expand output and hire more workers, especially in lower-skill roles.

Firm-level findings

Research from Canada, France, and Spain finds adopters grew employment and productivity. Dixon, Hong, and Wu (2021), Acemoglu et al. (2020), and Koch et al. (2019) report similar patterns: leaders gain market share and hire.

The reallocation effect

At the same time, lagging firms in the same industry often lose jobs as market share shifts. That creates local loss even when national income and growth rise.

Service sector example

A clear example comes from Japanese nursing homes. Eggleston, Lee, and Iizuka (2021) show devices reduced turnover and complemented staff, aided by subsidies.

Productivity and the squeeze

Higher productivity lowers prices and boosts consumer surplus, but it also raises pressure on less efficient firms. You should weigh whether a robot tax or broader capital reform best protects workers who face reallocation.

“Design targeted support for hurt workers rather than bluntly taxing tools.”

Robot Tax Debate: intention versus impact

You want to know whether the idea lives up to its promise. Supporters say a levy would protect human workers, stabilize payroll revenue, and fund retraining so people can move into new roles.

The promise is straightforward: revenue for reskilling, less immediate income loss for displaced workers, and a signal that employment matters in policy choices.

Protecting human workers and replacing payroll taxes: the promise

Proponents argue the levy would stop sudden income shocks and pay for rapid reemployment services and portable benefits.

That funding could ease transitions and help local economies absorb change without long spells of unemployment.

Investment drag, slower growth, fewer jobs: the risk

At the same time, research warns that a levy can discourage investment, especially in manufacturing where automation raises productivity.

If firms postpone purchases, investment and growth could slow, and the broader economy might see lower output and higher prices.

“Even the threat of a levy can delay purchases and change hiring timelines.”

- You’ll weigh short‑term support against long‑term capital formation and income.

- Evidence shows adopters often add employment, while laggards lose jobs through reallocation.

- Policy design matters: a broad capital approach may meet revenue goals with less unintended loss.

Your test: judge whether the intention aligns with impact, and look for complementary measures—like wage insurance and targeted subsidies—that protect workers without throttling innovation.

Taxing robots or taxing profits? What you actually incentivize

The choice between taxing inputs and taxing outcomes steers how firms invest and hire.

Profits, not the means of making them, is the IFR’s core line. European lawmakers rejected a special levy partly for competitiveness reasons. When you tax the device itself, companies may delay or relocate purchases to avoid the hit.

“Profits, not the means of making them” and competitiveness

Taxing profits keeps incentives neutral across methods. If productivity from automation raises income and output, the broader tax base grows and yields more revenue without singling out specific technology.

Revenue reality: how automation can expand the tax base

Look at the U.S. auto example: about 60,000 robots installed during 2010–2015 while the sector added roughly 230,000 jobs. Higher productivity can lift wages, corporate earnings, and overall revenue.

- Taxing tools can distort technology choices and cut investment.

- Profit taxation is simpler to administer and stays technology‑neutral.

- Targeted surcharges risk shrinking the economic pie and revenue base.

“Design taxation around outcomes, not inputs, to share gains without punishing specific deployments.”

For more on how automation affects employment and firm choices, see automation and jobs.

The U.S. tax code’s capital-labor bias and your policy choices

The U.S. code currently gives equipment and software big breaks, and that tilt shapes how firms hire and invest.

When capital faces ~5 percent and labor over 25 percent

Estimates suggest capital in software and equipment sees an effective rate near 5 percent. Meanwhile, taxes on labor often exceed 25 percent once payroll levies and lost deductions are counted.

That gap matters. Firms respond to after‑tax returns. Lower charges on capital encourage faster investment in machines and tools, and that shifts decisions about hiring and job design.

Leveling the field: broad capital taxation vs. targeted levies

You can choose a narrow levy on specific devices or a broad reform that treats all investment more evenly. Many economists argue the latter reduces distortions and is easier to administer.

- Single rate on all investments: simple and neutral; may raise employment and protect growth.

- Variable rates by elasticity: targeted, but complex and harder to implement.

- Adjust depreciation rules: a practical fix that affects many capital types, not just specific machines.

Analysis suggests eliminating the capital bias could lift employment by roughly 4 percent. You’ll weigh revenue and administrative ease, and decide if broad reform beats adding a narrow levy on certain tools.

“Design policy to reward productivity while avoiding rules that push investment offshore.”

Legal personality for AI and robots: do you need it to tax?

You’ll weigh whether giving some systems limited legal standing would actually solve liability and revenue questions.

The case for entity-like status is straightforward: proponents say a named legal shell for advanced artificial intelligence could sign contracts, hold insurance, and be billed directly. That, they argue, would make it easier to assign blame and collect revenues tied to automation.

Why supporters like the idea

Supporters point to complex, multi‑actor systems where tracing fault is hard. A legal persona would simplify payouts and streamline cross‑border claims during development and deployment.

The counterargument: we already tax equipment

Others note you tax machinery, software, and property now without personhood. The IFR warns against added bureaucracy that could slow innovation. ISO/TC 299 already gives global safety standards you can build on.

Practical guardrails instead of new persons

Instead of making entities, you could require auditable logs, mandatory insurance, and safety certification. Those tools keep humans accountable and avoid creating loopholes or offshore arbitrage in taxation.

“Targeted rules for use and responsibility beat wholesale legal personhood.”

- Assign liability to owners/operators, not to devices.

- Use certification, logs, and insurance to manage risk.

- Reserve legal personality only if autonomy truly outpaces accountability.

Worker-first alternatives that beat a robot tax

You can protect workers and raise incomes faster by funding reskilling, cutting hiring frictions, and using targeted subsidies rather than a blunt levy.

Fund reskilling with data-driven matching

Use tools like O*NET skill distances to match people to higher-paying roles (for example, moving brickmasons toward welding).

Channel revenue into training that links directly to openings, shortening the time between jobs and boosting income.

Cut labor frictions to boost mobility

Ease enforcement of non-competes and remove needless certification barriers. Nationally, NCAs limit mobility across many occupations.

When switching is easier, employment adjusts faster and workers face less career scarring.

Target subsidies where machines complement people

Japanese prefectures show how subsidies for nursing‑home devices cut turnover and raised productivity and benefits for staff.

Support capital and technology that amplify human work, not replace it.

- Prioritize workers: reskilling tied to real openings.

- Free movement: weaken non‑competes and speed hiring.

- Smart subsidies: fund tech that complements staff and lifts growth.

“Invest in matching, mobility, and targeted support to protect workers without throttling innovation.”

International coordination so U.S. firms—and workers—aren’t penalized

Coordinating policy with other countries is crucial if you want U.S. firms to keep investing at home.

Unilateral levies risk shifting investment and jobs abroad. Without coordination, companies may relocate automation purchases to friendlier jurisdictions. That move can erode domestic investment, slow growth, and hurt the very workers you aim to protect.

Avoiding a race to the bottom and offshoring of automation

When one country imposes a levy, others may undercut it to attract factories and suppliers. You’ll watch supply chains and companies chase lower adoption costs by moving equipment and hiring elsewhere.

Example: the U.S. auto sector installed many robots from 2010–2015 while adding jobs, showing competitiveness matters for both investment and employment.

Standards, safety, and governance: build on ISO/TC 299

Use global standards to align safety, reporting, and certification. The IFR and ISO/TC 299 offer a common baseline so countries don’t duplicate bureaucracy.

“Align taxation and standards so companies can plan, invest, and keep workers on the books.”

- You’ll favor targeted international agreements to reduce arbitrage.

- Consistent reporting across countries helps regulators measure effects on the economy and investment.

- Industry, governments, and workers need clarity on percent cost differences and timelines to hire with confidence.

Equity, revenue, and how you’d actually use a robot tax

Before you set a fee, you need a clear plan for how the money will stabilize households and local demand. Proposals typically direct revenue to unemployment insurance, elder care, education, and retraining so displaced workers regain income and purpose quickly.

Stabilizing demand: funding unemployment, elder care, and education

Use funds for fast, targeted supports: training grants, wage top-ups, and hiring subsidies tied to real openings. That reduces long spells of joblessness and keeps local spending steady.

Design questions: who pays—manufacturers or employers?

You’ll choose whether manufacturers face a point‑of‑sale levy or employers pay when a machine enters service. Each option changes incentives for investment and growth.

- You’ll map revenue to clear benefits so funds reach workers and jobs quickly.

- You’ll weigh administrative ease: plug into payroll or adjust depreciation schedules.

- You’ll consider trigger mechanisms to phase in levies only when measured displacement causes real loss.

“Design the levy to protect income and employment without choking investment and productivity.”

The politics of automation: your industry’s winners and losers

Politics shapes who pays when automation meets policy. You’ll see how narrow definitions — for example, excluding driverless forklifts — can shift burdens from factories to warehouses overnight.

Expect heavy lobbying. Companies will press to exclude their preferred gear, and trade groups will stress competitiveness. The EU Parliament already rejected a special levy, and the IFR warned it may hurt investment and growth.

You should note evidence from past years: firms that adopt automation often expand, while non‑adopters face local job loss. That dynamic fuels political fights over who bears the cost.

“Define the base clearly and tie relief to measurable worker outcomes.”

- Definitions decide winners: a narrow rule favors some industries over others.

- Companies will lobby for carve‑outs or credits tied to safety and retraining.

- Require transparent reporting so you can link any levy to real employment and worker outcomes.

Your test: tie any levy to objective metrics, allow firm‑level credits where development improves worker safety, and guard against capture so the policy protects workers without tipping firms to relocate capital.

Conclusion

A practical endgame balances revenue for displaced workers with incentives that keep investment and innovation strong. Evidence over the years shows adopters often raise productivity and add jobs, while non‑adopters lose out through reallocation.

You can pursue a targeted robot tax or broader reform. The IFR and the EU favored taxing profits over inputs, and U.S. capital‑labor bias suggests wide reform may work better than a narrow levy on equipment.

Focus revenue on benefits, reskilling, and wage support so workers regain income and employment quickly. Use standards, coordinate with other countries, and favor policies that keep the economy and innovation healthy.

Your checklist: strengthen mobility, align capital and labor taxes, fund training, and deploy incentives where machines complement people. That approach shields workers and keeps growth headed toward a fair future.